Warlord of the Bloodlands: The Chilling Story of Konstantin Dobrovolsky in German and Hungarian Service

A bombshell report exploded across the Daily Mail’s pages on June 27: the newly appointed head of MI6, Blaise Metreweli is the granddaughter of Konstantin Dobrovolsky, a man who operated as a Nazi spy chief in German-occupied Ukraine. And he didn’t just help the Germans, he also collaborated with Hungarian forces in one of the most brutal territories of the German-Soviet partisan war, the Chernihiv region.

Dubbed a local warlord in the so-called “bloodlands”, Dobrovolsky is now emerging from the shadows of history. Once just another nameless collaborator in military reports, he is suddenly given a face, a name, and a chilling legacy.

A ‘warlord’ under the Nazi shadow

As many as a million Soviet citizens served the Nazi war machine – but historians still debate who collaborated by choice and who simply bent to brutal necessity. In the case of Konstantin Dobrovolsky there’s little ambiguity. According to statements he made directly to German and Hungarian officers, his path to collaboration was deliberate and ideologically driven.

Born on May 9, 1906, into a wealthy Polish-German-Ukrainian landowning family, Dobrovolsky trained at the elite Vladimir Cadet Corps in Kyiv under the Russian Empire. But the Russian Civil War turned his world upside down – most of his relatives were murdered, and he spent years in hiding with his father. Even after 1922, he lived under false names to avoid persecution.

Trying to rebuild his life, Dobrovolsky enrolled at university – only to be arrested in 1926 for anti-Soviet activities and sentenced to ten years in prison. After his release from the Gulag in 1937, he worked in East Siberia, earned an engineering degree in Vladivostok in 1939, and was transferred to Ukraine’s Dnipro region in 1941. That same year, on August 4, he deserted the Red Army and joined the Germans, just months into the Nazi invasion.

From collaborator to self-styled ‘Hetman’: The rise of a mini-dictator

Initially tasked with overseeing captured Soviet tanks for an SS armored unit, Dobrovolsky soon made his way back to his homeland – the Sosnytsia district in Ukraine’s Chernihiv region. The Nazis took control of the area on September 6, 1941, and Dobrovolsky was granted permission to return two weeks later.

But German authority barely extended beyond main roads and garrison towns. In this power vacuum, Dobrovolsky seized control.

With no real German oversight, he formed a 300-man militia, arming them with abandoned Soviet weapons and feeding them by extorting nearby villages. By December 1941, his forces were operating not just in Sosnytsia but across 11 to 12 districts, carrying out what were euphemistically called “cleansing operations.”

This wasn’t an isolated case. Across western Ukraine, nationalist militias – sometimes linked to the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) – were also taking advantage of the chaotic German occupation to establish their own regimes of power.

But while civilian-run territories soon disbanded these rogue forces, in regions under military administration, such militiaspersisted well into 1942. German commanders simply didn’t have the manpower to replace them. A chilling January 1942 report by the 194th Field Administration Command (FK 194) admitted:

“Given the current troop shortage, the [Dobrovolsky-led] Ukrainian militia is indispensable. Without them, local mayors couldn’t function at all.”

'I am the police chief of left-bank Ukraine': A delusion of grandeur

Still, Dobrovolsky fought to keep his autonomy. Refusing to label his force “auxiliary police,” he called himself a hetman– an old Ukrainian title – or even the "Chief of Police for Left-Bank Ukraine." The latter earned him unwanted fame: Soviet partisans deemed him such a threat that they placed a 50,000-ruble bounty on his head – equivalent to £200,000 today, according to Daily Mail estimates.

Dobrovolsky flew the Ukrainian flag over his headquarters and referred to himself as the founder of a “free, independent Ukrainian state.” While he was never confirmed as an OUN member, he regularly made symbolic gestures to appeal to Ukrainian nationalists.

Hungarian troops stationed in the region were among those who noticed the growing nationalist fervour. In fact, on December 13, 1941, the Hungarian 32nd Infantry Regiment was ordered to disarm a Ukrainian militia in nearby Kozelets that was allegedly plotting to declare independence.

Despite his grandiose titles and nationalist leanings, Dobrovolsky remained a man of convenience, working with any power that would allow him to maintain control – even if it meant cozying up to Nazi commanders.

An unholy alliance: Dobrovolsky and the Hungarian army

Though Dobrovolsky’s unit operated independently for months, in December 1941 it was officially placed under the authority of the 197th Field Administration Command (FK 197). He then vowed to wage a war “against bandits” – a chilling euphemism for anti-Nazi partisans.

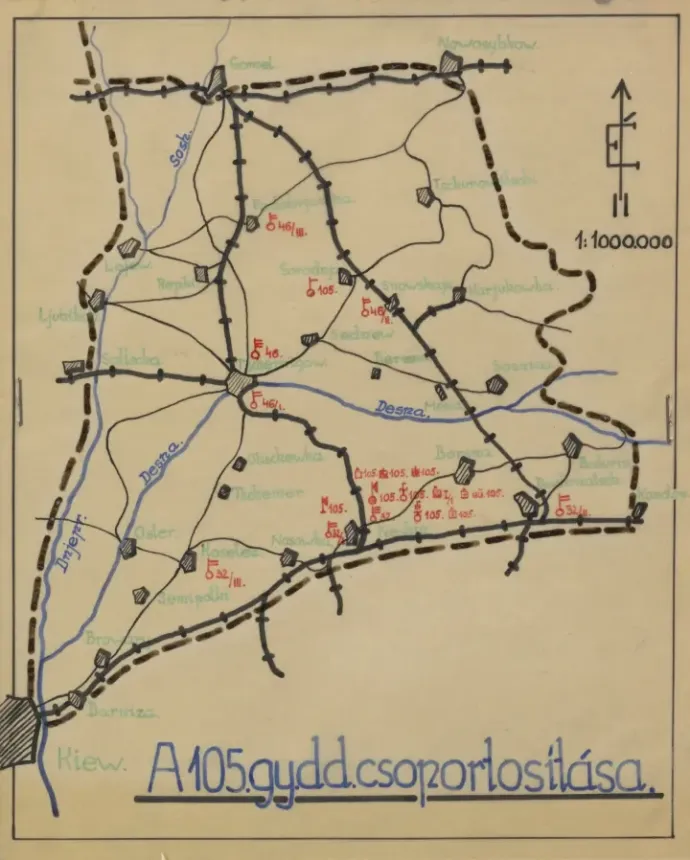

With Soviet partisan leader Oleksiy Fedorov gaining strength in the region, the Germans had limited resources. Besides Dobrovolsky’s militia, their only backup was the Hungarian 105th Infantry Brigade – which was deployed in the region at the time. And so began Dobrovolsky’s collaboration with Hungarian occupying forces.

The ‘capable, iron-fisted, trustworthy’ commander who won the Hungarians’ respect – and led a reign of terror

"The value of a militia depends entirely on whether its units are led by genuinely capable, iron-fisted, pure-intentioned and absolutely reliable commanders."

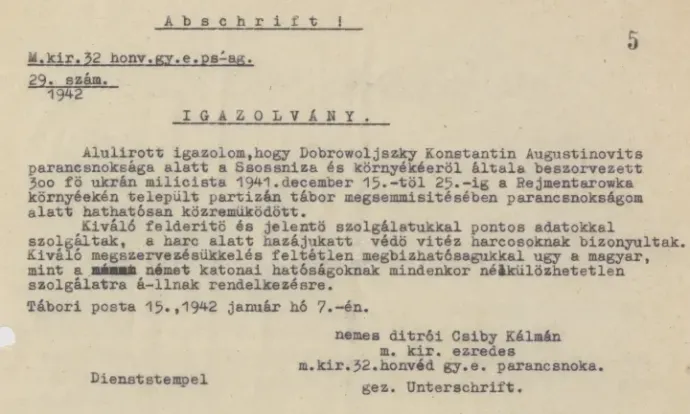

So read a 1942 Hungarian army field manual on counterinsurgency and collaboration. And in the eyes of Colonel Kálmán Csiby, commander of the Hungarian 32nd Infantry Regiment, Konstantin Dobrovolsky fit the bill perfectly.

An official certificate issued by Csiby in January 1942 confirmed what was already clear to his men: this so-called "Hetman" of the Ukrainian steppe wasn’t just a useful ally – he was a trusted partner in arms. One postwar testimony even suggested a personal fondness had grown between the Hungarian colonel and the Ukrainian warlord, with records of feasting and mutual visits after joint operations.

According to Dobrovolsky himself, he had already begun fighting alongside the Hungarians as early as November 1941, though records suggest this likely began in early December. He operated under the command of Lieutenant Gyula Berencsváry, who led the 32/6 Company. It was during this operation, near the village of Kudrovka, that the warlord sustained a leg wound after his horse was shot from under him.

We have little information about the results of the joint “partisan hunt” in early December, but based on the surviving sources, the operation involved massacres of the civilian population. For instance, Berencsváry, the Hungarian lieutenant reported on December 10, 1941, that he had ordered the execution of 25 Jews after a search of the village of Makoshino. This is hardly surprising given that his company was part of the 32nd Regiment’s II Battalion – known as one of the most aggressive Hungarian units deployed against Soviet partisans.

The ‘Butcher of Sosnytsia’ joins Hungary’s deadliest unit

According to German reports, this battalion accounted for nearly a quarter of all partisan deaths inflicted by the entire Hungarian 105th Infantry Brigade during the brutal winter of 1941–42, eliminating 1,240 individuals by March 1942 alone.

Berencsváry himself appears to have served as Dobrovolsky’s key liaison during the infamous Reimentarivka–Koriukivka operations, where the two forces cooperated closely.

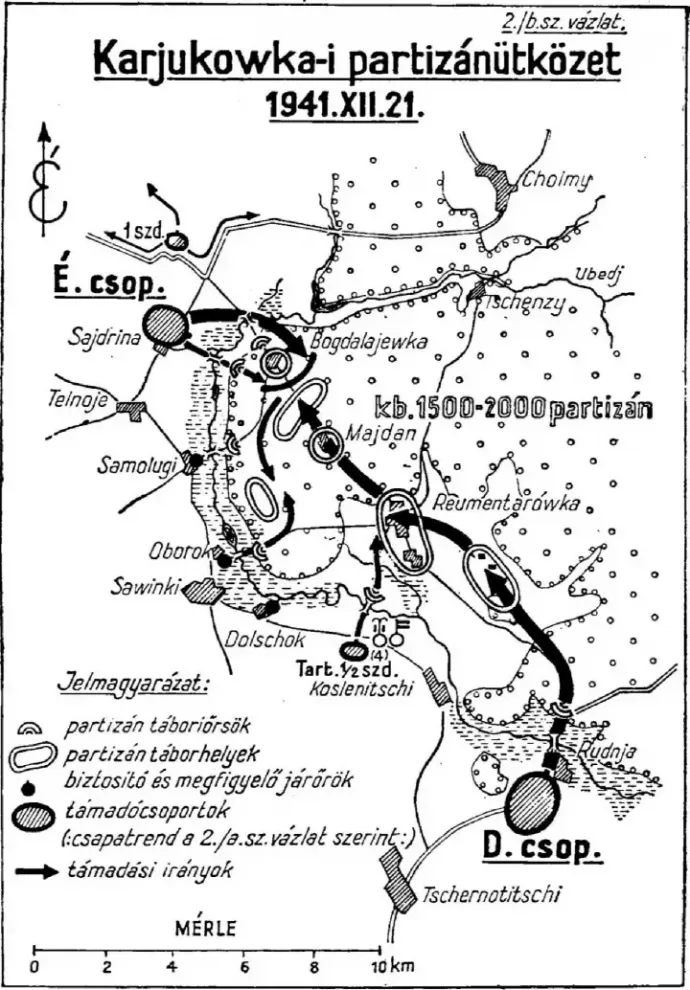

Between December 17 and 25, 1941, Hungarian and Ukrainian forces conducted their bloodiest "cleansing operation". The newly deployed 105th Infantry Brigade had been ordered to neutralise partisan groups believed to be consolidating under the command of the famed Soviet leader Oleksiy Fedorov. Though both Hungarian and German forces grossly overestimated the number of partisans, the under-equipped and poorly trained Hungarian units struggled nonetheless.

A coordinated assault – and a ruthless intelligence network

On December 17, the 32nd Infantry was tasked with surrounding Reimentarivka from north and south to prevent any partisan escaping. Dobrovolsky’s militia, consisting of 80 men in cavalry and 220 in infantry, was folded into the main southern attack force based in Sosnytsia.

Contemporary reports highlight the Ukrainians’ value as scouts. On December 19, it was Dobrovolsky’s men, working alongside Berencsváry’s company, who identified the location of the partisans, leading to a full-scale assault.

We lack direct evidence of Dobrovolsky’s intelligence-gathering methods, but certain grim clues remain. His men, intimately familiar with the region, benefited from ruthless tactics and deep local fear. Surviving documents from the Sosnytsia police archives reveal that villagers were legally bound under threat of death to report any partisan activity. In many cases, the reports included chilling annotations stating that non-compliant informants had been executed.

Torture, execution, and the making of an accomplished militia leader

Captured partisans fared even worse. Reports describe interrogations involving steel wire beatings, red-hot iron rods heated in fireplaces, and burning cigarettes pressed into bare skin. These acts weren’t anomalies – they were standard procedure under Dobrovolsky’s rule.

Unsurprisingly, Soviet partisan propaganda dubbed him "The Butcher of Sosnytsia" – and with good reason. He wasn’t merely a warlord. He was a man whose collaboration with the Axis powers left a trail of blood, broken bodies, and terrorised villages in his wake.

And yet, to the Hungarian high command, he remained a “capable, reliable, iron-willed commander.”

The massacre at Reimentarivka

"The operation was a complete success."

So proclaimed a 1942 Hungarian military report about the brutal Reimentarivka operation – an operation that left hundreds dead, most of them civilians, in what has since been described as one of the first large-scale mass killingscarried out by Hungarian troops in Ukraine.

According to conflicting reports, between 700 and 1,200 so-called ‘partisans’ were killed, while attacker losses amounted to just a tenth of that. But 60% of those losses were sustained by Dobrovolsky’s Ukrainian militia – with 11 killed, 27 wounded and 9 missing, nearly one-sixth of his force.

Yet even Hungarian sources admitted that most of the actual partisans escaped, slipping away northeast just before the full assault. In reality, most of the “eliminated partisans” were likely ordinary civilians – locals accused of “supporting bandits” or providing aid to resistance fighters.

When Reimentarivka was captured on December 21, 1941, not a single Hungarian soldier was lost. And yet, 114 civilians were killed and nearly 300 homes were burned to the ground. It marked the first time the Hungarian army carried out a massacre with over 100 civilian victims in the region.

Who did the killing? The militia’s role in mass execution and looting

Though surviving records don’t fully clarify how directly Dobrovolsky’s militiamen participated in the killings, Soviet partisan propaganda at the time squarely blamed him, not the Hungarians. While this might be an exaggeration – Hungarian assault engineers and flame-grenade squads clearly inflicted the greatest losses – Dobrovolsky’s men played a crucial supporting role.

His unit was split into two: one group guided the Hungarian troops during the advance, while the other secured their rear. Postwar testimonies say the second group wasn’t just in charge of supplies and “clearing the battlefield” – they also looted the village.

"After the bloodbath, Dobrovolsky and 150 of his men began systematically robbing the local population". recalled Warrant Officer Jenő Kövesy, adjutant of the 32nd Battalion.

"They collected furs, carpets, and valuables, loaded them onto a wagon, and transported everything to Sosnytsia. Even the surviving livestock was driven off."

This wasn’t an isolated event. Dobrovolsky's home was reportedly filled with carpets, linens, silk scarves and fur coats looted from mass execution sites.

More killings, more atrocities – and a dinner celebration

After the main force rested, smaller Hungarian units and Dobrovolsky’s militia continued “mop-up operations” between December 22–24. One report listed villages such as Oborki, Samotuhy, and Tel'ne, along with the forests east of them, as locations where “resistant partisan bands” were encountered.

A Hungarian field report stated that on December 22, the 105th Infantry Brigade eliminated a “90-strong Jewish band”accused of supplying food to partisans.

Dobrovolsky, ever eager to demonstrate loyalty to the Axis, boasted of his anti-Semitism in official biographies sent to the German command. He even claimed he had been exiled to Siberia for his hatred of Jews, and that during the Battle of Kyiv, he had personally participated in mass executions.

Warrant Officer Vince Lantai, who served in the 36/II Battalion, recalled Dobrovolsky bragging that he had “personally executed 400 Jews and partisans in four hours.”

While German and Soviet documents mention his role in the Holocaust in northeastern Ukraine only sporadically, local witnesses and survivors paint a much darker picture. Given that Dobrovolsky’s militia was the only organized auxiliary force in the Chernihiv region, it is highly likely that they took part in numerous mass killings of Jews under the guise of anti-partisan operations.

Though Jewish population density was lower in this region than in western Ukraine, survivors were not spared brutality. The Sosnytsia police kept a list of Jews to be “shot on sight” – including infants just months old. Rapes and murders were so appalling that even the German 194th Field Administration Command expressed shock at the treatment of Jewish women prior to execution.

Ukrainian researchers estimate that 4,000 Jews were killed in the Chernihiv region – over half of them during the final quarter of 1941.

Rape, execution, and beheadings: A chilling portrait of systematic terror

In northeast Ukraine, the extermination of Jews and partisan warfare were deeply entwined. Contemporary military language often described the Reimentarivka operation through a virulently antisemitic lens – portraying General “Orlenko” (an alias for Oleksiy Fedorov) as a “Jewish Bolshevik bandit” and claiming the Jewish population of Koriukivka was “inciting rebellion.” The truth is that the only "crime" of many Jews was to flee into the forests in an attempt to survive.

Even intelligence-gathering became a tool of anti-Semitic violence. On December 17, the Hungarian 32nd Battalion arrived in Chornotychi, where Ukrainian militiamen had already detained two Jewish men and four Jewish women. Sergeant Balázs Dénes Egyedy later described the moment in a published account:

“We didn’t do anything!” the Jews protested.

“No? Just told the partisans where and when the Hungarian soldiers were arriving?” the guards spat back. […]

At dawn, the militiamen gave a command, and the prisoners were marched away in silence. An hour later, the militia returned—without them. No one asked what had happened. It was all too familiar by then in Ukraine.”

Another report on the Battle of Koriukivka claimed that 264 prisoners – mostly Jews – were executed following interrogation. Details remain unknown, but many were almost certainly murdered by Dobrovolsky’s men. That evening, Dobrovolsky hosted a celebratory dinner for the Hungarian officers.

According to Lieutenant Colonel Aladár Töttösy, who gave a statement in 1950:

“Before the meal, Dobrovolsky staged a cavalry display. A captured communist was tied to a post. Dobrovolsky mounted a horse, drew a sword, and – galloping at full speed – decapitated the man with a single swing.”

Such scenes weren’t rare. When Soviet forces retook the area in 1943, investigators documented at least 300 executionscarried out in the courtyard of the Sosnytsia police station, most of them by gunshot or sword. Victims were either buried in mass graves or dumped beneath the frozen Desna River.

The fall of Dobrovolsky

"They say there's a Ukrainian hetman who considers it a matter of honour to personally capture and shoot every last partisan. He leads our troops on horseback, and on the town square, he strikes down Bolshevik captives with his sword from the saddle. They’re tossed straight into the pit and buried, whether dead or still breathing — people whispered that the ground kept moving for hours afterwards.”

So wrote Hungarian archeologist Gyula László in his wartime diary, from faraway Kyiv, some 200 kilometres from the terror-stricken region of Sosnytsia.

By early 1942, stories – and likely photographs – of Dobrovolsky's savagery were spreading beyond the ranks of the 32nd Infantry Regiment. But German command was divided. While FK 197 praised his effectiveness and even tasked him with building an auxiliary police force in Nizhyn, others grew increasingly uneasy. His infamous Reimentarivka purgeprompted suggestions to the Army Group South rear-area command that more Ukrainian reconnaissance units similar to his should be created.

Yet as control of the northern Chernihiv Oblast shifted to FK 194, the tone changed drastically. This command sought to distance itself from the unruly militia chief. Orders were issued: if Dobrovolsky or his men crossed into their territory, local collaborators were not to obey him.

From power to pariah: The gradual erosion of a warlord’s empire

By January 1942, FK 197 began rolling out a formalised structure of auxiliary guard service (Hiwa) and auxiliary police (Hipo) even in previously unregulated areas. With his experience and position as a Hiwa inspector, Dobrovolsky was reluctantly folded into the bureaucracy. But the reins were tightening.

Much of his former dominion was handed to neighbouring commands. By April 1942, his militia was dissolved, its members absorbed into the official auxiliary guard service. Although Dobrovolsky retained his title as inspector, he was sidelined in July from further organising authority. He was reassigned to the intelligence (Ic) division of Army Group South, and later to Army Group B.

Now registered under code V-30, Dobrovolsky was demoted from warlord to informant – albeit an effective one. His reports on Soviet partisan activity were detailed and valuable. But it wasn’t enough for a man used to ruling with a blade and iron fist.

His self-submitted résumés and petitions to the German command between 1942–1943 reveal a deeply resentful figure, obsessively trumpeting his contributions to anti-partisan operations in Northeastern Ukraine.

The final humiliation came in November 1942. Returning to Sosnytsia under Hungarian papers, he found himself the subject of a formal complaint by the new head of local law enforcement – the very post he had once absolute control over. In a cruel reversal of fate, the once-feared “hetman” was now accused of abuse of power by the people he had terrorised.

Abuse, looting, and personal killings: Even the Germans grew uneasy

The investigation exposed deeply uncomfortable truths. Among them: personal vendetta killings, looting disguised as partisan warfare, and threats made against German-appointed mayors and auxiliary police. The scandal, though never prosecuted, clearly marked the end of Dobrovolsky’s reign.

The German command sided with the new police chief. Although Dobrovolsky wasn’t punished for his crimes, he was deemed unsuitable for leadership. They recommended his transfer to another sector or redeployment to frontline anti-partisan operations.

On May 5, 1943, he was formally dismissed from the intelligence service.

By May 25, he was assigned to organise and lead a Cossack hunter-squadron, likely continuing operations against partisans in the rear. The final known assessment of him, dated November 19, 1943, described him chillingly:

“Captain D[obrovolsky] is a reliable comrade and a talented bandit fighter.”

His name appears just once more in German records, in February 1944, leading a “Jagdkommando” – a hunter unit – under the name “Doprowolski.” By September 1944, Soviet-language newspapers in Berlin had already listed him as missing.

His ultimate fate remains unknown.

"The Bolsheviks turned him into a bloodthirsty beast"

This disturbing description comes from Warrant Officer Vince Lantai, who served with Dobrovolsky and kept a wartime diary. Yet, depending on one’s worldview, the former militia chief can be interpreted in drastically different lights.

To his own mind, Dobrovolsky was a vengeful crusader against the (Judeo-)Bolshevik system that had exiled and persecuted him. To Soviet partisans, he was simply a reactionary thug and a disgraced nobleman, bent on reclaiming feudal authority with brute force.

Modern memory politics complicates the picture further. On one hand, the Ukrainian OUN's legacy of chauvinism and antisemitism casts doubt on the motives of nationalist militias like Dobrovolsky’s. On the other, the escalating brutality of partisan warfare added a layer of viciousness to all sides of the conflict. But more than ideology, it was structural chaos that allowed Dobrovolsky’s violent reign to flourish.

Nazi-occupied Ukraine was marked by lawlessness, unregulated lower-level authority, and a tacit tolerance for extreme violence – especially when the targets were Jews, Communists, or suspected partisans. These groups aligned perfectly with the enemy archetypes of the occupying Germans and their Hungarian allies. As such, Dobrovolsky’s atrocities were not only accepted – they were encouraged.

In the end, his downfall had little to do with his methods, and everything to do with his uncontrolled ambition. He refused to play by Germans’ rules, and that – more than the blood on his hands – sealed his fate.

The author is a historian and a researcher at the Institute for Violence Research in Budapest.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!