Starting in October, exactly six months before the Hungarian parliamentary elections, just when the campaign would switch into high gear, Alphabet and Meta (Google, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram) will stop displaying political and public service ads in the EU.

In recent elections, Hungarian political forces have been relying heavily on social media ads as a campaign tool, so now, without it, online campaigning will have to be done in a completely new way.

The big question is how effectively the various players will be able to adapt to the new rules of the game and whether they will be able to use the remaining, limited opportunities available to reach people with their messages. More specifically, since Fidesz has been the dominant player in online advertising (since it had the money to do so), the big question is what the ruling party will do when this campaign weapon is taken away from them.

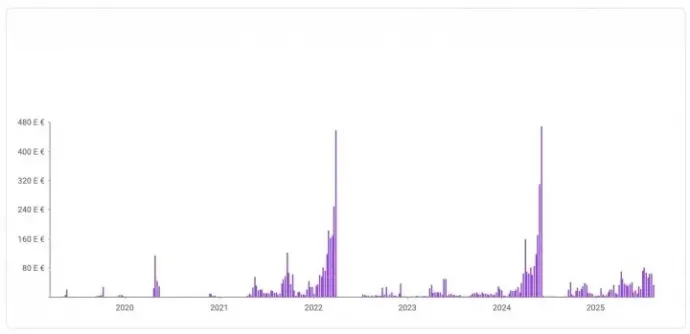

The importance of this tool in Hungarian political marketing is best illustrated by the chart below, which shows the money spent on political ads in Hungarian on YouTube by the week, going back as far as 2019:

The two spikes, marking a spending between 150-200 thousand euros for a few weeks, then peaking at nearly 450,000 euros indicate the spending leading up to the 2022 parliamentary elections and the 2024 municipal/EP elections. At today's exchange rate, €450,000 is nearly 180 million forints, and if we calculate with the price of 2-3 forints per view, we find that

in the run-up to the elections, Fidesz's various ads about the opposition presenting a danger for the country, or claiming that if Fidesz doesn't win, there will for sure be a nuclear war, were streamed around ten million times a day.

The overall politics-related spending from Hungary on YouTube ads over the past six years was 2.6 billion forints, of which Fidesz spent around 600 million, with the Prime Minister's Office, Megafon, and Mediaworks spending 300 million each.

Things are even worse on Facebook. In 2022, during the official 50-day campaign season, more than 3 billion forints were spent on the campaign (two-thirds of which was spent on hammering Fidesz's messages), and during the 30 days leading up to the 2024 elections, this amount was 1.7 billion forints. These are staggering amounts even by European standards. But Hungarian political circles have been eager to pay for ads on Facebook during non-campaign periods as well: over the past six years, more than 16 billion forints were spent on such advertisements, which amounts to an average of roughly 7 million forints per day.

The biggest advertisers are Fidesz (approx. 2.2 billion HUF), the pro-government media empire Mediaworks (2.1 billion HUF), Megafon and its affiliates (2.9 billion HUF), and the Hungarian government itself (860 million). And then there are a bunch of organisations affiliated with Fidesz, such as the Civil Cooperation Forum (CÖF), the Movement of National Resistance (NEM) and the Center for Fundamental Rights, each having spent around 100 million forints.

It could also present a problem for Fidesz that, in addition to social media, one of the ways another very important channel for their propaganda, the pro-government online media maintains its readership is through Facebook ads. We have already mentioned Mediaworks' bill of nearly 2.5 billion forints, but the public broadcaster also spent quite a hefty amount on advertising, with Híradó.hu having paid 258 million forints for Facebook ads. In the last 90 days, Híradó.hu spent 18 million forints on promoting its posts and articles on Facebook – during this time, the page reached an average of 46,000 readers per day and generated a total of 8 million page views. It's impossible to determine how much of this is directly related to advertising, as only the number of ad impressions is publicly available, the number of clicks isn't – but it's probably not insignificant.

Another example is Magyar Nemzet, the flagship of Fidesz propaganda and the government's number one mouthpiece: in the last three months, it spent 39 million forints on advertising, while averaging 195,000 readers per day and a total of 46 million page views. For context, Telex's figures for the same period were as follows: an average of 580,000 readers per day, a total of 252 million page views, and 76,000 forints worth of Facebook ads.

This is what will not be available for Fidesz's campaign strategists for the 2026 elections, while all indications suggest that this is likely to be the fiercest contest of the last 15 years, which – at least as things presently stand – they are heading into from a disadvantage. Tisza won't miss social media advertising that much (and obviously, neither will ordinary users of the internet), as they have spent a fraction of what Fidesz has on this: since the party was founded, they have spent 58 million forints on Facebook and 19 million on YouTube. To put it in perspective, this is more than ten million forints less than what Megafon has spent so far on sponsoring the Facebook posts of only one of their influencers (Kopasz oszt).

What is Fidesz going to do in this situation? How is it going to replace its campaign weapon, which has been so actively used and is about to be disabled? We called in Péter Krekó and Csaba Molnár, experts at the research institute Political Capital, to help us find some possible answers.

One and a half months until the shop closes

Google had already indicated at the end of last year that it would stop running political ads, and Facebook's announcement at the end of July was not entirely unexpected either, since the company had been hinting at such a move for several years, saying that such ads only cause problems, they harm user experience, and the revenue they generate is a mere drop in the ocean. So there was (or would have been) enough time to come up with a plan for the few remaining months, while advertising was still possible.

It would be an obvious move to quickly spend the entire advertising budget allocated for the year and, as much as possible, boost the size and activity of their follower base so that in October, once the brave new, ad-free world arrives, they can at least start with that much of an advantage. There are signs that this is happening. Political Capital's weekly political ad monitor clearly shows that there has been a surge in Facebook ads linked to Fidesz since the end of July (Meta made its announcement on July 25). The chart below shows the Orbán regime's weekly spending on political advertising on Meta platforms between December 29, 2024, and August 23, 2025. The different colors represent government-controlled media, government-controlled proxy organizations, Fidesz and its politicians, and government organizations respectively.

Curiously enough, this is not visible at all in the case of Megafon, which is considered the biggest Fidesz-affiliated advertiser. Its monthly advertising bill is still around 30-40 million, just as it was during the spring months. Since it was established, Megafon has spent billions of forints of its ‘non-public funds’ on promoting approximately 20-25 pages, and was able to produce a total of two well-known figures (Dániel Deák and Dániel Bohár), who have each gained a significant following of over 100,000 followers and have a serious, stable presence at the very forefront of the world of Hungarian Facebook propaganda.

Would it make sense for Fidesz to keep them and their organic reach and keep using them, while quietly letting the ones with a smaller following go? Not necessarily. "In the Fidesz-run, multi-player and, to some extent, diverse online disinformation ecosystem, there is a greater chance that ads from individual sites will slip through the imperfect ad filtering systems of social media platforms as non-political ads, and Fidesz is certain to experiment with this in the future. At the same time, the pages with a smaller following are likely to maintain their reinforcing and activating effect on their own camp, while a significant part of the currently used campaign tools are aimed at least as much inward as they are outward," says Péter Krekó.

Moreover, one of Fidesz's fundamental principles is that instead of admitting mistakes, bad decisions, or defeat, they double their efforts. In light of this, it will be interesting to see what they do with the recently launched morning podcast show, Harcosok órája (The Hour of Fighters). We recently wrote about this new magic weapon of communication, noting that its episodes organically attract around 20-30,000 viewers, which is then inflated to hundreds of thousands with Facebook ads. It will be pretty embarrassing if viewership suddenly drops to a tenth of the current one in October and they will have to come up with an explanation for it.

The Fight Club could be a somewhat effective substitute for advertising. "It is no coincidence that the instructions in the Fight Club group have been mainly about sharing, liking, and commenting on Viktor Orbán's Facebook posts, rather than, for example, engaging in debates in the comments section under Péter Magyar's posts. This may – to some extent – compensate for the lost adverts, although the effect of this is quite limited. Meta is more likely to show the content that has been "boosted" this way to other users, but this mainly means users with similar interests as the Fight Club activists. Paid ads, on the other hand, can be used relatively well to target people based on areas of interest and which demographic group they belong to. The reach of the posts boosted this way is also lower than that of advertisements, which can be displayed for hundreds of thousands of users in the case of an ad costing millions,” explains Csaba Molnár.

Looking at it from this vantage point, the function of the digital civic circles (DPK) is different. “In my view, the role of DPKs is not primarily to dissemination the message, but rather to bring together and coordinate an already active and committed community, and through them mobilize potential voters and reinforce the perception that the ruling party has a significant mass base and that its election victory is a foregone conclusion.”

Could the Russians be planning on getting involved?

Could we expect a similar level of Russian interference in our elections, as was the case in Romania earlier this year? The question has been hanging in the air, especially since the Russian intelligence service has made it unmistakably clear whose side they are on in this contest. "So far, there has been no real need for an intensive Russian intervention in communication in Hungary, as the government has itself been spreading pro-Russian messages rather effectively.

At the same time, the stakes in the upcoming election may be higher for Russia, so it is not realistic to assume that the Russian state will not try to provide assistance to the Hungarian government in the online space through its proxies.

For instance, the Russian troll network that we have examined in our previous analyses could assist in astroturfing (presenting political initiatives as citizens' grassroot initiatives)," says Péter Krekó.

But even if there is some kind of interference, it will most certainly not have the same drastic results as it did in Romania, where the far-right Călin Georgescu's support was boosted from practically zero to 23 percent, which was enough for him to win the first round of the (later annulled) presidential election, mainly thanks to a Russian manipulation campaign conducted on TikTok.

Indeed, all indications (although it is quite difficult to research such things with scientific rigor) suggest that social media alone can only do so much to change people's political opinions. The online campaign is but a spark—one that found a powder keg in Romania, i.e., a combination of several factors: the general mood, the relative lack of regulation on TikTok, and Georgescu's obscurity. Obviously, it is much easier to turn social discontent into support for a completely new player than for a government that has been ruling with virtually absolute power for 15 years.

If one thinks about it though, the meteoric rise of figures with no political past has been a common story all over in recent years, starting with Donald Trump and Emmanuel Macron, through Javier Milei and Volodymyr Zelensky, and even all the way to Péter Magyar in Hungary. Social media manipulation, however extensive, is not necessary and is not in itself a sufficient trigger for launching such a career.

"The reason why the Romanian case was so effective was that the Russian propaganda was able to piggyback on an already established, organic network of popular influencers, often with no political affiliations, who are considered credible by their own audiences. Thus, the channeling of political messages looked much less like a campaign and more like organic content," Péter Krekó says. “The situation is different in Hungary: Fidesz has not really needed influencers so far, because the government's media empire itself fulfills this function, and does so with a massive reach. Following the partial failure of Megafon, Fidesz gave up on building up its own influencers, and has been trying to turn politicians into influencers as well as trying to recruit actual influencers.”

In the void that will follow the disappearance of political ads, Fidesz will desperately need the support of credible and popular figures and their followers, and they can afford to buy it—but the situation is not that simple. Hungarian influencers have already been embarrassed a few times by getting too close to Fidesz, and it remains questionable whether they can afford to compromise their credibility.

"It would be a serious risk for mainstream figures who are popular among young people to openly spread political propaganda.

The reputation and long-term success of high-reach influencers depends on their ability to appeal to a wide audience, and this could limit their reach. At the same time, Fidesz can pick and choose from those in the mid-range (and is already doing so)," says Krekó.

"Of course, there are exceptions: figures whose political loyalties are already known, such as Norbi Schobert or certain musicians. They have a big reach, but it does not necessarily extend to the younger generation. In short, while this was a successful Russian strategy in Romania, we cannot expect it to be as effective in Hungary.

This is primarily because the Hungarian equivalents of the conspiritualist “lifestyle influencers” who provided one of Georgescu's main pillars of support and were able to organically align themselves with his pseudoscientific, conspiracy-theory-based, anti-vaccination messages, etc., cannot find similar elements in Fidesz's ideology. The far-right Mi Hazánk, which already latched onto such themes in the previous election, would be a much more natural environment for them.

Money is no problem

Another viable option for Fidesz to compensate for the loss of advertising would be to purchase and promote Facebook pages with large followings that are currently dormant, or smaller, but active apolitical pages, and use these to spread its messages. There are still plenty of pages from the early days of Facebook in Hungary with hundreds of thousands of followers, which have been dormant for quite some time (1, 2, 3, 4 are just a few random examples), and would thus be perfectly suited for this purpose. In fact we have just reported a few days ago that the admin of an Instagram page known for posting strange, harmless memes has suddenly switched to hardcore Fidesz propaganda and has been trying to purchase other meme pages for unreasonable amounts of money.

Beyond all that, only creativity can limit Fidesz's opportunities in the world of political ad-free social media. The network of personalized smear pages presented before the 2022 election is still there, and we would be surprised if they didn't revive it. And, of course, there are quite a few Fidesz politicians who have a significant following on Facebook even without advertising. By now, we have seen several examples showing that the Fidesz team loves mimicking Trump, which means that Orbán's podcast and interview tour is likely to continue. And who knows what else they will come up with…

What is certain, however, is that come October, without political advertising, social media will be a much more comfortable and peaceful place than it has been at any time in the past 4-5 years. And that in itself is quite a big deal.

(The figures quoted in the article for advertising expenditure, readership and other data reflect the situation on August 14.)

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!