I put myself through the eternal-youth seeking multimillionaire's routine – it was one of the saddest months of my life

“Máté!!! Would you be up for trying that 'Don’t Die' guy’s routine? I totally would, but there’s no way in hell I could live on that crap. So I thought of you. :D”

Such was the content of the email (suspiciously lacking a subject line) that was waiting for me one January morning from our Lifestyle editor, Lívia Liptai. At the time, Bryan Johnson’s Netflix documentary/advertisement had just come out, and it suggested the perfect idea for the next installment of my human-experiment series: Máté, the immortal. Little did I know, that just a few months later that email would have me thinking of Lívia with mild resentment nearly every morning around 9am. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

People are split on the idea of immortality, but if someone could guarantee we’d spend it in perfect health and fitness, I think a lot more of us would give it a shot. Personally, I’d only sign up for something like that if I could stay physically and mentally at the top of my game. Just think how thrilling it would be to go back a few hundred – or thousand – years. If I became immortal today, I’d get to witness the very events that future time-travel dreamers would only be able to fantasize about.

Of course, I’m not the first person to contemplate this, and throughout history, many have searched for an antidote for death. And in a way, I think they succeeded remarkably. Back in the 19th century, people lived to an average age of just 28.5 to 32 years old (pulled down, of course, by the high child mortality rate), while today life expectancy is around 72 – 73. The reason? Simply put: advances in modern medicine, better hygiene, and the ever-increasing availability of food.

Recognizing similar patterns, a great deal of doctors and scientists today are working hard to push the limits of a healthy lifespan. But experimenting on humans isn’t easy. Aside from the ethical restrictions, it’s also practically impossible to tell, within the span of a few months, how a treatment might affect someone’s health twenty years down the line.

Still, longevity research is booming, and even in Hungary, private clinics are now offering such treatments. For now, the therapies that hopefully extend our lives are mostly limited to these paid options, and one of their most enthusiastic voices is Bryan Johnson.

Johnson is a multimillionaire who made a fortune selling his company, Braintree, to PayPal. By his own admission, for decades he lived the stereotypical, rather unhealthy lifestyle of VC investors and startup owners: long hours, hard partying, heavy drinking – until the day when he found himself contemplating suicide. That’s when he came to the conclusion that his brain was the enemy, and he shouldn’t listen to it. From that point on, he devoted all his time, energy, and money to focusing on his body – keeping his organs as young as possible. He believes death is just a small technical problem we can solve.

To that end, he subjects himself to nearly every medical test imaginable – many of them regularly – to find out what he's getting too much or too little of and adjusts his workouts and diet accordingly. Almost every minute of his day is planned to make sure he spends his time efficiently, eats at the optimal moment, and gets enough exercise. Roughly, his routine resembles the following:

- wake up around 5am;

- drink a special concoction;

- work out for an hour or so;

- eat some kind of pudding-like food;

- work a bit;

- “and what about second breakfast?”;

- a little more work;

- lunch around 11am;

- work a bit again;

- take a half-hour walk, chat, and rest;

- and by 8:30pm, eyes closed and sleeping within minutes.

Those are just the big milestones, of course. He also sticks to a pretty elaborate morning hair and skincare routine and takes dozens of vitamins and supplements throughout the day.

The plan

Johnson’s logic reflects exactly what I mentioned earlier about increased life expectancy: there are things we know are bad for us, which he cuts out, and things we know are good, which he maximizes. And one of the pillars of his personal brand is that he’s “the world's most measured human.” Based on all those measurements, his team of experts determines what and how much he should or shouldn’t consume, and what he should do. That means he takes several dozen supplement pills every single day.

Our original plan was for me to get some of the more important and accessible tests done at the start of the month and again at the end, so we could actually see whether anything changed in those thirty days. Somehow I was also going to get ahold of all the supplements so that I could mimic Johnson’s routine as closely as possible.

The only problem was, perhaps I would be able to replicate his diet, but his bank account was a totally different story. The tests alone would’ve cost hundreds of thousands of forints, and a month’s supply of supplements and vitamins came to 123,000 forints (and even then I couldn’t find everything in Hungary). You can have too much of a good thing anyway, so we didn’t even bother submitting this version of the plan to Telex’s financial team. It probably wouldn’t have been the most sensible way to spend our readers’ donations.

So we came up with Plan 2.0: I’d portray a normal person who decides to turn their life around after discovering Johnson and his protocol, trying to follow the influencer-entrepreneur within the limits of reason. So over the course of a month I stuck to Johnson's daily routine (minus the countless pills and special treatments) and prepared my meals from his “cookbook” – for lack of a better word. On top of that, I didn’t drink any alcohol or sugary drinks (only water and black tea), ate practically no chocolate (we’ll get back to that later), and cut out all snacks except for one, maybe two apples a day and a handful of nuts (strictly unsalted and unroasted).

Still, I couldn’t avoid buying something from Johnson’s store. His daily routine involves a drink powder called Longevity Mix and a protein pudding powder called Longevity Protein – both part of his Blueprint supplement line. We managed to get ahold of them, though it wasn’t easy. They weren’t cheap either, so I doubt most people would spend that kind of money on them every month. They were 50,000 forints including shipping, and the closest place to Hungary where you can get them is the Czech Republic. But since they’ve been staples of Johnson’s diet for years, we decided they were essential to the experiment.

The experiment had three goals: to find out if this lifestyle is actually enjoyable and sustainable; to see whether anything would really change in thirty days; and to get a bit healthier and lose some weight in the process – something I’d been feeling I needed for a while.

Tomorrow starts tonight

I started the experiment over the summer, though a sudden bout of indigestion delayed the kickoff by a few days. Still, there was a silver lining: the weight loss started earlier than expected. The plan was for my mornings to look like this:

- wake up at 5;

- at 5:10 weigh myself and check my blood pressure;

- by 5:25, I’m in the kitchen mixing my fruity drink powder;

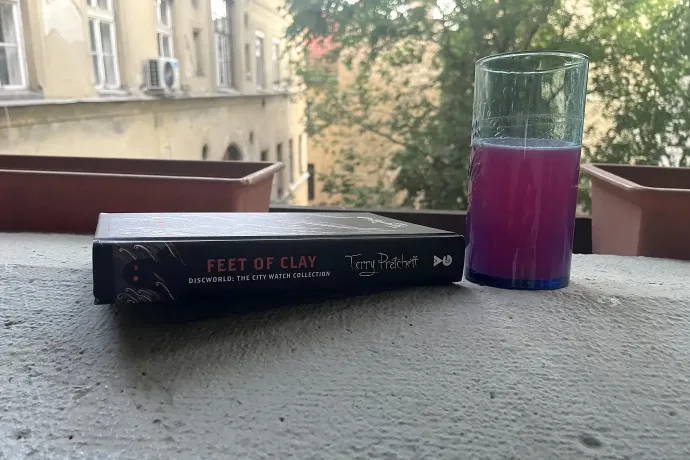

- sit out on the balcony and sip it while reading;

- then 40-60 minutes of running or rowing;

- a shower before 7, prepare the pudding;

- work starts at 7am.

I started the experiment at 97.6 kilos, with a BMI of 26.5, 22% body fat, and 39.1 kilos of muscle. The numbers, apart from my weight, are only moderately reliable – a smart scale at home is nowhere near as accurate as a professional one – so I wasn’t after exact data, just the general direction of change.

One of Johnson’s main ideas is that every day actually begins the night before – and honestly, I can’t really argue with that. It’s obvious our performance takes a hit when we crash into bed at 3am, possibly drunk, only to toss and turn for four hours before stumbling into work half-dead the next morning.

That’s why Johnson starts winding down around 8pm every night, does his final evening rituals, and closes his eyes by 8:30 – supposedly falling asleep within minutes. He’s proud of the perfect scores he gets from his sleep-tracking app and breaks the routine so rarely that when he does, he immediately shares it with his followers.

Since I don’t have an evening skincare ritual, my goal was to be in bed by eight without any screens, read a bit, and clear my mind. At 8:30pm, I’d start an audiobook with a ten-minute timer, and according to my watch, I managed to fall asleep within half an hour almost every night. When I didn’t though, it was pure hell.

It’s easy for Johnson to say everyone should sleep in 19 degrees Celsius when he lives in a multimillion-dollar home custom-built for this lifestyle. According to my bedroom thermometer, the temperature barely dipped below 23 degrees, so I was nowhere near ideal conditions. And that’s not even mentioning the fact that Johnson can black out his room completely, while my yellow curtains still perfectly let in light from the setting sun at half past eight. In the end I wouldn't even close them because the sunlight helped me get up at five the next morning anyway.

Even so, most of the time I managed to fall asleep quickly and usually woke up at five feeling rested – even on the first morning. But there were three or four nights when, for example, the neighbors were being loud and I just couldn’t fall asleep for hours. I still had to get up at five, though, and I felt wrung out like a dishrag.

I tracked my sleep quality with a smartwatch the whole time, and while I didn’t manage Johnson’s impressive 100% sleep score, the sleep part mostly worked out. At dawn, when almost everyone’s still asleep, the city is amazing: there were hardly any people in the park when I went running, and life just felt calmer. Of course, that only lasts a few hours before the city wakes up. This wasn’t exactly a surprise, since I’d already tried getting up at five every day for a month once before.

Still, waking up early wasn't all peaches and cream: sure, it sets a good pace for the day, and since I had more time in the morning before work, I felt more productive, but for me this would only work long-term if everyone else switched to it too. Having people over was a nightmare. Of course they came after work, around seven. No matter how good the mood was, I had to call it a night between eight and half past eight. While the others were cracking up in the living room, I was left to cry myself to sleep.

Not to mention my day was shorter than usual, too. Normally I get up around seven or eight and go to bed around midnight. That gives me about 16-17 active hours a day. By comparison, if I wake up at five and have to start winding down at 8pm, closing my eyes at 8:30, then at best I’m awake 15.5 hours a day. So the experiment basically took away 30 hours of my life. And I could feel the difference: since I had to go to bed comically early, we couldn’t plan anything. I had to cancel my plans three or four times because they would’ve started too late. I spent a lot more time at home, basically alone – because even though my girlfriend was home, our schedules were so out of sync that it felt more like we were just sharing a space together rather than a life.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating

Before I started all this, I was mostly optimistic – especially after watching a bunch of Johnson’s videos where he talks about how comfortable his chosen lifestyle is. However, there was one thing about it I didn't learn until about halfway into the experiment: he doesn't actually do his own cooking – a private chef handles that. By then I wasn’t really even surprised, because I’d already realized weeks prior that cooking wasn't a joy anymore but rather my biggest chore.

Johnson shared a PDF detailing his daily meal plans, all precisely calibrated to provide him optimal nutrition. Alongside the two powdered things I mentioned earlier, he eats a cooked vegetable mix every day plus one of the listed main dishes. In the videos he always says how delicious everything is, but that’s a huge lie – and I say this as someone who knows taste is a very subjective thing. With food, I’m usually of the mind “different strokes for different folks” (heck, even I like pineapple pizza), but what Johnson, his advisors, and his experts have done to the institution of cooking is almost unforgivable.

Let’s start with the first meal of the day, the Longevity Mix drink powder. Johnson claims it’s heavenly, but also warns not to let it sit too long because the powder sinks to the bottom. After waking up early, this was my first real encounter with his Blueprint world, and to be honest, it didn’t win me over. It tastes like someone tried to imitate blood-orange flavor without ever having tried one. It’s basically artificial fruit flavor. I never really developed a taste for it either. Every morning I just sadly stared off into the distance while stirring the scoop of powder in my drink. This part of the routine was, frankly, almost pointless. I used the same little handheld milk frother as Johnson, but no matter how long I ran it, the powder never fully dissolved. Every morning I’d end up with a layer of it sticking to my mouth. I really tried to adjust it in every which way – more water, less water, colder, warmer – but nothing seemed to help.

So it’s expensive, not that tasty, and unpleasant to drink, and yet apparently, Johnson’s team designed it to replace a bunch of supplement pills. If you hate swallowing tablets, maybe even this artificial-tasting powder water is an improvement. All in all, it's not that it tastes horrible – it's just depressingly artificial. You can tell taste wasn’t a priority at all – and that mindset pretty much holds true for his entire diet.

The next meal was the Longevity Nutty Protein pudding mix. This time it was obvious what flavor they were going for – that same artificial nutty taste you find in tons of snacks and processed foods. Real nuts have their own natural sweetness, but that was completely missing here, and unsweetened almond milk did nothing to make the breakfast any more enjoyable.

This became a recurring theme: while eating that pudding, not only did I feel all the nasty stuff that causes aging slowly leaving my body, but hope, optimism, and zest for life also left along with it. To make things worse, the powder tended to clump up in the cold milk, so sometimes I’d bite into a pocket of dry powder – something that didn't exactly elevate the experience of the meal. At least I figured out that if I warmed up the milk a bit before mixing, it dissolved more easily (though still not perfectly).

By about the third breakfast I decided that it is possible to have too much of a good thing – and this was definitely one of those cases. From then on, I started adding some walnuts, almonds, cashews, and hazelnuts, plus a handful of frozen blueberries. If sugar had been allowed, I would’ve thrown in a spoonful of honey too, but that was off-limits. With these extras, the pudding went from tolerable to actually pretty good – a respectable 6 out of 10.

I managed to improve things even further when I went looking for a Johnson-approved snack. Nuts and fruit were a given – and lifesavers – but Johnson also allows chocolate, as long as it meets his strict standards. Naturally, his store sells cocoa powder too, but I wasn’t about to spend 14,000 forints on 400 grams, so I bought a bar of 100% dark chocolate instead. I quickly learned that I can go as high as 85%, but 100% is just too much, too pure. So I gave up on that idea, especially since Johnson himself doesn’t approve of the brand’s 75% version either. Still, I didn’t want to let the chocolate go to waste, so I broke a few squares into my morning pudding, which really elevated the whole experience – up to a solid 7.5 out of 10. Of course, that made it far from budget-friendly.

The third and second-to-last dish of the day was something called “Super Veggie” – a cooked vegetable mix. I was supposed to eat it around nine, and that’s when I often found myself thinking bitterly of Lívia. Anyone with the slightest experience in the kitchen can probably already spot the problem just by reading the recipe: 45 grams of beluga lentils, 250 grams of broccoli, 150 grams of cauliflower, 1 clove of garlic, 3 grams of ginger, 1 lime, 1 tablespoon cumin powder, 1 tablespoon apple cider vinegar, 1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil (I skipped the mushrooms – ew). And not a hint of seasoning. Each of those vegetables is a gas factory on its own, but somehow that particular side effect didn’t show up during the experiment. The real issue was that you basically had to boil everything together, then douse it in oil, vinegar, lime juice, and cumin – and that’s it. That’s the whole dish.

Two major problems here: first, a portion is about half a kilo of boiled vegetables – way too much. There were times I sat there chewing for half an hour just to get through it all. The pictures Johnson posts with his meals are purely illustrative (not that he ever says so), but the actual portions are massive – and nowhere near appetizing.

And that brings us to the second problem: in its original form, the recipe is mind-numbingly boring. The documentary Ratatouille explains perfectly how flavors work: sometimes they complement each other, sometimes they clash, and depending on the ingredients and preparation, you can create incredible combinations. Here’s what I wrote to my editor, Zsolt Hanula after I first tasted Super Veggie:

“This whole thing is nonsense. Holy crap, this is awful. I don’t think it was even supposed to taste good – the whole idea seems to be suffering. It’s brutal. I can literally feel myself getting sadder.”

That had never happened to me before. Back when I did an experiment allowing AI to dictate my life, I walked into a non-existent festival with a smile on my face. Another time I even wore the same boxer shorts for a month, but at least I didn’t have to waste time in the morning deciding what to wear. But now, by the third meal of the first day, I was already complaining to anyone who’d listen that this was impossible, that I was giving up, and that after a week I’d write: “Dear readers, I’m sorry for letting everyone down, but this is no way to live.” Don’t worry – I held strong and made it through. Here’s how Johnson himself describes the Super Veggie:

“A small note on the taste of Super Veggie. The food I eat is divine to me; one of the most exciting parts of my day. When someone starts this program, they might need some time to adjust, and some people may want to experiment with the recipe or texture. Blueprint goes against every social norm, which understandably provokes certain reactions that draw those very lines.”

You rarely see a product that has to come with a disclaimer saying, “Yes, I know it’s bad, but that’s okay.” Make no mistake: even though Johnson generously shares the recipes for free (which, to be fair, is nice of him), these are still products. In certain U.S. cities, you can order ready-made meals from his site – not cheap ones either: the pudding costs $16, and the main dishes range from $10 to $17, or about 3,300–5,600 forints at the time of this article's writing. He even sells extra virgin olive oil – 750 milliliters for 12,000 forints. Ironically, he named it Snake Oil – the traditional term for bogus miracle cures sold by fraudsters.

Super Veggie isn’t inedible, but it’ll drain your will to live. It doesn’t even have the decency to taste bad. It’s just mind-numbingly boring, which I’d argue is an even greater sin. Still, since I only had to fight back tears and not my gag reflex, I ate it every morning without modification. But it was just too much, so I started eating half portions. I'd do anything for the readers, but I’m still human – I have my limits.

After two and a half disappointments out of three, I was a bit nervous about making lunch. My family, friends, and colleagues had a blast listening to me rant about all this, so I’ve concluded the world is mostly full of hobby sadists. But anyone who’s tired of hearing me whine for five paragraphs can breathe a sigh of relief: among Johnson’s main course recipes, I actually found quite a few good ones. With a few tweaks, some of them could easily become part of a normal weekly rotation.

Although his diet seems to have changed quite a bit since, the recipe booklet still available on his official site is the one I used. Johnson eats vegan, but he’s said in several videos that it’s just his personal choice – everyone can do what they want. Since I didn’t buy any supplements, I decided to eat meat during the experiment – not all the time, and with minimal seasoning. So every day I ate something very vegetable-heavy and sometimes even tasty, and once or twice a week I added a bit of chicken breast, pork loin, or salmon.

The blood orange and fennel salad, beet poke, chickpea curry, and Buddha Bowl were all hits. Since the experiment ended, I’ve cooked them several times again – in fact, as I write this, there’s a bowl of Buddha Bowl heating up in the microwave. Unfortunately, though, Johnson and his team couldn’t resist messing with people who actually enjoy food, and came up with something called a “cabbage steak.”

I know I said I’m forgiving when it comes to food, but there's a limit to everything. A steak is meat. A one-inch-thick, mildly sweet slice of cabbage, seasoned only with chipotle powder, paprika, and onion powder, is not steak. In fact, I’d go as far as to say it’s not even food. The edges burned to a crisp before the middle even softened. It was truly awful. Not even the side dish could save it: the sweet potato, bland almond milk, cinnamon, and nutmeg together made something closer to a dessert purée, and paired with the cabbage, they mercilessly crush your taste buds – and your spirit. It was the only meal we simply couldn’t down and had to throw away. After a while I tried taking photos that made the dishes look better for the article, but the fact that I refused to ever cook this monstrosity again just to get a proper shot says it all.

By the way, every dish was huge – I either ate them over the course of two days or split them between two people. The logistics also weren't helped by the fact that sometimes I couldn’t find all the ingredients. The greengrocers and supermarkets around Budapest Keleti station don’t sell Japanese sweet potatoes, shallots were hard to find, and Swiss chard was nowhere to be seen, so I had to get creative.

And not just with substitutions, but to make the dishes a bit more exciting too. After one particularly dry lunch, my girlfriend summed it up perfectly: “This guy’s basically eating a massive side dish for lunch.” Couldn’t have said it better myself. This past summer Telex writer Bori Ács pointed out that a salad without dressing is just a pile of leaves – a sentiment which I couldn't agree more with. Luckily, that’s an easy fix. Johnson’s recipes aren’t inherently inedible or beyond saving – like the Super Veggie.

Before this experiment – back when I was blissfully ignorant and aging uncontrollably – I often meal-prepped for several days at a time. That luxury disappeared the moment I started the challenge. Sure, in theory I could have cooked most of the meals in advance, but I simply didn’t have enough pots, bowls, or fridge space for all those vegetables and five days’ worth of lunches. So almost every afternoon turned into the same routine: finish work, cook, wash dishes, go to bed. That’s just not sustainable long term – at least not for me. The Super Veggie was the only one I could prep ahead, but with all the raw ingredients, the first few tries easily took an hour. Even once I got the hang of it, each batch still took half an hour. That’s no issue for Johnson – he’s got people doing it for him. All he has to do is eat it, though that seems like punishment in itself. But for an average person who would rather do literally anything else with their time, this lifestyle isn’t sustainable without serious mental or emotional damage.

Here are a few thoughts I jotted down during my suffering:

– Flavors? What for? That’s just a bourgeois indulgence.

– With every bite, I felt a little sadder.

– No wonder it takes half an hour to eat this stuff – it's only 'edible' in theory.

– Why start the day with punishment?

– Even though my last meal is at 11, I’m rarely hungry – only a bit before bed. What’s worse is I constantly crave flavor. It’s almost physical pain.

Great in theory, less so in practice

Of course, that’s just my personal take, so I asked dietitian and nutrition expert Róbert Pilling what he thought of the whole project. I gave him a detailed breakdown of what and how I ate, and roughly what changes I noticed.

“From a nutritional science perspective, it's actually nicely structured and thought out. The recipes are good, the recommendations respect moderation, and it’s great that Johnson says it’s okay to deviate from them,” he said.

I wanted to know whether cutting out so many things all at once could harm me. Luckily, Pilling said no – especially not short term – since it’s actually a very healthy diet. It’s rich in plant-based foods, high in fiber, and low in calories, so after a month of sticking to it strictly, I probably did my body some good.

But he also noted the downside – the countless supplements Johnson takes every day, even recommending others to do so too:

“It’s clear that no matter how good this diet is, it doesn’t meet the body’s needs in the long run. It makes you wonder whether it’s worth it at all, just for the dozens of pills that he takes.”

The problem isn’t just having to swallow that many tablets (which is a challenge in itself) but also the fact that no one really knows how all those supplement ingredients interact with each other. When it comes to food, we already have a pretty good idea of how things interact with our bodies and with each other. However, supplements are a different story, especially when someone takes thirty of them a day. There’s no guarantee they won’t clash or cause unwanted interactions. At that point, the expert actually praised me for not taking any supplements myself – he wouldn’t have recommended it either.

What makes things even more complicated is that Johnson also takes prescription medication alongside his supplements. Some of it is for a congenital hormonal disorder (e.g. thyroid hormones), which is perfectly reasonable, but it still raises concerns. It might be that everything he takes works together in perfect harmony, both in the short- and long-term. For someone else, however, especially if they’re not taking the same medication, the effects could be very different, even harmful.

Not to mention that the human body is an incredibly complex system, so there’s simply no way to say that what works for one person will automatically work for another. And if someone has a pre-existing condition, or is on other medication, that could interfere too.

“That’s where the credibility of this method starts to falter. Johnson’s diet is sustained by strict, regular lab testing, something that the average person can’t afford to do. Further, it would be completely pointless if a million people started doing full lab panels every two weeks. What he describes doesn’t come from large-scale population studies; it’s all based on his own lab data and maintained around his individual results,” said Pilling.

“For an ordinary person, I definitely wouldn’t recommend following this diet long-term. As even his own website mentions, there’s no promise or proof that it will work for anyone else.”

For instance, some people are genetically predisposed to have trouble breaking down broccoli. For them, the Super Veggie would have a completely different effect – “for all we know, this diet could be an absolute disaster for them.” If we really wanted to be scientific about it, everyone who dreams of a “super diet” would need to get a genetic test to see how their body metabolizes different substances, and then build their diet around that. It also matters which dishes someone chooses and when, because they don’t all have the same macro balance. So maybe your body actually needs sweet potato that day, but instead you have beet salad for lunch – that small change could throw your system slightly off balance.

The dietitian also pointed out that one big problem today is how inconsistently and hurriedly people generally eat. A lot of trendy diets “work” simply because they force people into a bit of routine. Having a structured system like Johnson’s can be an advantage, but it becomes counterproductive if the gaps between meals are too long.

He wasn’t surprised, for example, that I performed worse during those early-morning workouts – my body isn’t built to handle intense training after 17 hours of fasting. It didn’t help that my last meal was eight or nine hours before bedtime; since this is a low-carb diet, it made sense that I sometimes felt sluggish at the end of harder days. Our brain runs primarily on carbohydrates, after all, and it's our most energy-hungry organ. Without enough carb intake, concentration and attention both drop. “That’s why you shouldn’t have such long breaks between meals – especially between the last one of the day and the first of the next,” Pilling said.

He didn’t think the diet would be harmful in the short term – like one month, for example – and said I shouldn’t expect withdrawal symptoms. Still, he wasn’t surprised that I had a few mood swings (to put it lightly) because of the sudden change. When someone essentially moves into a new environment and cuts themselves off from all sources of pleasure, it can be jarring. That’s why extreme lifestyle changes usually fail – people strip away all their joys so abruptly that their body starts to rebel on a subconscious level, and after a few days or weeks, they just give up and “just raid the fridge.”

I’ll admit, I was tempted too – but what kept me going was the thought that a month of suffering would make a better story than quitting after three days. But one question remained: if I keep this up, will I live forever too?

“I’m not convinced that just keeping all your lab values perfectly in range means you’ll live forever. I can even believe his results match those of an 18-year-old – but aging is a much more complex process than that.” “For me, that's where the theory falls apart,” said Pilling. He acknowledged that Johnson’s lab results and physical stats are impressive, but he can easily imagine a point where the body just gives out and collapses under the strain.

Of course, neither of us wish anything bad on Johnson, but he wouldn’t be the first person to live an extremely healthy life only to be suddenly diagnosed with cancer – and despite years of effort, still face a fatal outcome. And then there are all the unpredictable factors: the snapping of a mooring line, a careless driver, or an electric shock from a power system failure – and there goes immortality.

A sound mind in a sound body

After gloomily sipping my morning fruit drink, it was time to work out. The plan was to move every day, but that’s not how it worked out. Some mornings my body just wanted to sit and keep reading because I was exhausted – and Johnson himself says we should listen to our bodies. Even so, I managed to work out four or five times a week, which I’m pretty proud of, and I genuinely felt much better afterward. Of course, that’s hardly groundbreaking – probably no one needs me to tell them that exercise is good for you. But what surprised me was that, while my previous workout routine had just been about maintaining my level, by June I could actually see I was improving.

Naturally, I couldn’t replicate Johnson’s training either – and neither could the hypothetical average person from my "Plan 2.0." Mainly because the multi-millionaire has his own private home gym. He talks a lot about his workouts and has uploaded several instructional videos to YouTube, but that doesn’t help much if you don’t have the same setup – or if you need to spend an hour or more commuting just to exercise. So I stuck to running and the rowing machine. The running didn’t last long. It was much easier and more satisfying to just hop on the rower and put on an episode of House M.D. That became my morning workout routine.

If you usually train once or twice a week (maybe three times on a good week) there’s no diet in the world that will suddenly let you start working out hard every day without consequences. After one particularly rough morning, I wrote this in my notes: “The fourth rowing session in a row was tragic. I only managed 25 minutes. Maybe it’s not healthy to work out 17 hours after my last meal. I feel completely drained in the mornings. It’s also possible I’m pushing myself too hard for my current fitness level. Even House couldn’t help like he did yesterday.”

I know a good workout plan should balance cardio and strength training, and Johnson once shared what seemed to be one of his older routines, but since his schedule calls for exercising between 5:30 and 6:30 a.m., I didn’t have time to get to a gym. That’s when I understood: maybe being a multimillionaire is worth it. So I just focused on doing some sort of workout, whatever form it took. That felt truer to the spirit of my imaginary “average person” – someone just trying to live a bit healthier.

There’s really nothing bad to say about this part: moving feels good, especially once you find something you actually enjoy. That’s not always easy, but it’s worth it, and once you find your thing, it’s just about building the routine – though that’s probably the hardest part. I think I've been managing it pretty well: aside from a short break in July, I’ve been working out four times a week. I've been able to maintain some of the progress from the experiment and even improve on certain results.

So what’s the outcome?

After a month, I looked at what had changed, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, quite a lot had improved. By the end of June, I weighed 92.7 kilos, so I’d lost nearly five kilos. My body fat percentage dropped to 20.2. It’s worth repeating that home scales aren’t particularly reliable, and unless you get a professional body analysis, it’s better to focus on the trend, not the numbers. Mine showed an overall decrease, which is good news, given I’d been torturing myself for a month. Interestingly, my muscle mass also dropped, down to 38.3 kilos.

So I’d call the experiment a partial success, but I’ve maintained those values since, and they’re still improving, just much more slowly. If nothing else, this whole thing gave me the kick I needed to start moving toward a healthier lifestyle – one I’m still trying to follow, even if not as obsessively as Johnson.

This is what I’d tell anyone tempted to dive headfirst into the multimillionaire’s lifestyle: for most people, it’s probably not a great idea to do things exactly like Johnson. It’s expensive, isolating, and there’s no guarantee it’ll work the same way for anyone else. More than once during the experiment, it hit me that no matter how much I tortured myself, since I wasn’t getting the same level of testing and care as Johnson, odds are, I won’t end up living forever.

In fact, I’ll go so far as to say neither will Johnson, I suspect. Try as he might, he can’t control every tiny variable in life. He could slip during a workout, choke on a pill, or get struck by lightning. Someone could break into his house and shoot him.

That’s why, to me, what he’s doing isn’t exactly logical. A long life only makes sense if you can actually enjoy it. Otherwise, what’s the point? Of course, everyone’s different, but to me there’s no meaning in merely breathing and existing just to figure out how to keep breathing tomorrow. The problem with Johnson’s Don’t Die project shows up most clearly in his meals – they constitute the perfect metaphor for the whole protocol: dry, joyless, repetitive, designed only to tick the boxes his team currently considers important.

I’d like to think that in some parts of the world, we’ve already moved past that mindset of just trying to survive. Back when we lived in caves and weren’t sure if we’d eat tomorrow, focusing on the “optimal diet” made sense. But it's been a few years since then, and now many of us can afford to think of eating as a source of pleasure or an experience to be savored. Eating is one of those essential things we’ve managed to make genuinely enjoyable over the centuries. This kind of sterile nutrition spits in the face of everyone who worked hard to make food delicious.

But what really got to me was how lonely it made me feel.

I didn’t have assistants who could adjust to my schedule, or doctors examining me whenever I was free. Like I mentioned, I had to cancel plans several times, and even when something did work out, I had to call it an early night. At our traditional summer department barbecue, for example, I had to leave after just an hour and a half to get home before it was lights out. And in that short time, I couldn’t enjoy the incredible spread – just a few olives and a bit of salad, which was already breaking my strict diet.

It was a lonely month, even with my girlfriend by my side. We barely saw each other: maybe over lunch if we both worked from home, or briefly in the early evening. Weekends were dedicated to working out and cooking, and traveling was definitely out of the question. I can imagine that might not sound so bad to some people, but I get my energy from spending time with loved ones and friends, and in that sense, June was brutally draining.

It was only partially compatible with my work. It didn’t disrupt my daily schedule too much, as luckily, it doesn’t matter much if I start working at seven or nine. But since I was on my own schedule (and solitude was kind of the theme of the month), I often ended up working well over eight hours because I never had a fixed start time.

On the other hand, it did come in handy when Israel attacked Iran in mid-June. My early mornings meant I could jump straight into the news with the morning editor and help launch our live coverage right away.

Our work also includes an on-call system, and I mostly end up with the evening slots. Since I had to be asleep by 8:30 during the experiment, I specifically asked not to be slated for such times in June. But this wouldn’t be sustainable long-term. It’s hard to wake up and be functional at 5am when I had been on the computer until after midnight. But the biggest change the experiment brought was that I worked at least one or two hours more every day that month.

Is life good like this?

I think Johnson’s starting from the right place: take stock of your life and see what’s not bringing any real benefit: the things that are just giving short-term satisfaction while being harmful in the long run. Once you see that, decide what you’re willing to let go of. During the experiment, for instance, I pretty much gave up fast food – and I plan to stick with that. But if you realize you’ve gotten hooked on something, it’s best to ease out of it slowly, otherwise you risk swinging too far the other way.

A few years ago, when I tried dopamine fasting for a similar article, I learned something interesting: people who lose control and develop addictions often end up getting addicted to control itself once they quit. They try to make up for the past by obsessively managing every aspect of their lives. I would have liked to ask Johnson about that, but he never responded to any of my interview requests.

Don’t get me wrong – I don't claim or even think that Johnson’s a fraud. The more interviews with him I read and the more videos I watched, the clearer it became that he genuinely believes in what he’s doing. I think he really does enjoy that blood orange drink mix. With that said, I will never believe him (or anyone) that he actually likes the Super Veggie. Yes, he’s built a huge business around his immortality project, and yes, he promotes his products whenever he can.

But he also constantly says that no one has to do things exactly his way. He encourages everyone to find their own path, and often adds that people don’t have to buy from him – they can get similar stuff elsewhere. The point, he says, is to start moving toward a healthier life within your own physical and financial limits, and to spend money on quality, meaningful products.

It was so strange to see, read, and hear all this, that it's only now, months later, that my cynicism started breaking through the polished, positive image his media appearances had built in my mind. If someone feels compelled to change their life, they’re usually ready to take big, drastic steps – especially if they’re under some inner pressure driving them to do so. And if someone in that state of mind encounters Johnson, who presents himself as a man whose biomarkers show that he’s

- fit,

- healthy,

- well-rested,

- and, “in the top one percent for nighttime erections,”

and they see that his entire protocol is basically free and open-source, how could they not feel pressured to think, “If it worked for this guy, maybe it’ll work for me too,” and go buy something from the Blueprint store? I think they would. But, as I said, maybe I’m just a bit cynical.

In the end, it all comes down to self-control. Do I have enough of it to refrain from consuming harmful things? Do I have enough of it to overcome my laziness and go work out? Do I have enough self-control to cook instead of stuffing myself with junk food? And, if I manage all that, do I have enough self-control to resist the urge to buy half the stuff in Johnson’s shop?

It’s great that someone’s out there encouraging people to live healthier lives, and in that sense, I think what Johnson’s doing deserves recognition. But I’m not sure how much scientific value his project really has. Science relies on large sample sizes and reproducible results. Johnson only studies himself, and his team only gives him things they believe will extend his life in particular. Meanwhile, his followers – who, like those of any influencer, can sometimes veer toward cultish devotion – see that his numbers are improving and assume that the closer they stick to his routine, the better their own results will be.

That’s not necessarily true. Not everyone’s body works the same way. Financially, the whole thing doesn’t add up for most people either. The Blueprint store sells everything from starter powders and supplements to nuts, shampoos, and T-shirts, but someone living on the median Hungarian income couldn’t afford to buy new supplies every month. That’s assuming they even get past the first hurdle, since the store doesn’t ship to Hungary.

And even if you skip the powders, fresh vegetables alone are insanely expensive. In June, I spent noticeably more on food and utilities than in a typical month. That might not sound so bad, but keep in mind, I spent the entire month just working, cooking, and going to bed. No restaurants, no nights out with friends, no going to the movies. Even without a single luxury, I still managed to spend a small fortune on raw vegetables.

So what’s the takeaway? Simply this: if you’re an ordinary person thinking about changing your lifestyle, don’t start by doing exactly what Johnson does – it’ll make you lose all enthusiasm for, well… life. Even Johnson himself says that everyone should improve their life at their own pace – and that’s one piece of advice worth taking. Self-control is important, but micromanaging every part of your existence won’t make your life better. And a long life only matters if you actually get to enjoy it.