The smell of fuel alone was said to have been enough to get the VeloSolex going. The legendary French moped used to be popular with students, housewives, priests, nuns, Parisian intellectuals and civil servants alike, and even celebrities such as Brigitte Bardot were fans. Many consider it to be as much a symbol of France as baguettes or the Citroën 2CV. The fact that there are still operational models around the world today, nearly four decades after production ceased, is thanks to a family-run manufactory in the Hungarian village of Berettyóújfalu.

In today's age of electric bicycles and scooters, it is easy to find a means of transport that allows one to cover short distances cheaply and quickly without much effort. Back in the day, when the rapid development of motorization began, this role was filled by scooters and mopeds, which proved to be practical in both urban and rural environments.

Immediately after WW2, buying a car was still uncommon in France, and there were fuel supply issues as well, and gasoline was only available on ration cards. In this environment, a lightweight, inexpensive moped with low fuel consumption was bound to be a success. The VeloSolex, which resembled a more robust bicycle and could also be pedal-operated, was launched in 1946. With a top speed of around 40 kilometers per hour, the 49cc small engine could travel 100 kilometers on 1.4 liters of gasoline. Due to its low speed, the French nicknamed the VeloSolex "tailwind" because, in their opinion, the engine did not help the bike any more than the wind does when it gives a bicycle a push from behind.

After producing just over eight million VeloSolexes, the Saint Quentin plant finally closed in 1988, and it seemed that this would be the end of the small motorbike. It was then that Sándor Gáthy-Kiss, a retired pharmaceutical factory director who had emigrated from Hungary to France in 1956, saw the potential for further production and bought the factory's dismantled production line for 24 million francs.

Gáthy-Kiss wanted to relaunch production in Debrecen, but was unable to find a suitable site there. However, he found the Magyar Gördülőcsapágy Művek (MGM) factory in Berettyóújfalu to be suited to his purposes. After the fall of communism, MGM lost its Soviet markets, so Gáthy-Kiss founded a joint venture with MGM called Cyklon Kft. and took on the approximately 800 workers employed there, even though he knew that he would only be able to keep the production economical with about 300 employees.

Gáthy-Kiss conducted a successful advertising campaign, for example, ten university students rode motorcycles assembled in Hungary using French parts all the way to Paris, proving the durability and viability of the small motorcycles marketed in Hungary under the name Cyklon. This earned the French-Hungarian entrepreneur several orders, and at the 1991 Budapest International Fair, he received about a thousand pre-orders for the motorcycle, as it was being offered at a price discounted by 5,500 forints. Its price of 24,000 forints was still about 10,000 forints cheaper than the small Babetta motorcycles, which were also popular in Hungary at the time.

Despite having received tens of thousands of orders, there was never any real manufacturing going on in Berettyóújfalu, they only operated as an assembly plant, and Gáthy-Kiss found the early days of Hungarian capitalism suffocating. In 1995, he told Valóság magazine that bureaucracy had made it impossible for him to obtain the necessary loans on the best terms, and that neither the state privatization agency nor MGM had really tried to help his business along. Of course, his inexperience and poor market assessment also contributed to the failure. The company was constantly short of money and was unable to pay wages, until finally, in August 1994, the situation escalated to the point where the workers seized the factory so that at least the production line's value could cover their wages and Gáthy-Kiss wouldn't be able to take it away.

Cyklon Kft. declared bankruptcy, but there were still many who saw potential in the production of the VeloSolex – or rather the S3800, as the original name had been transferred to a subsidiary of Fiat. A French company was the first to restart production, assembling thousands of motorbikes per year, but they failed. Over the course of a few years, the company had several Hungarian owners who tried to continue the business, but no one was able to gain a foothold for long, even though they were only manufacturing parts.

"From the time the factory was established until the end, my father worked as the head of engineering, and around 2000, when everyone else had given up, he saw the potential in manufacturing spare parts. We started getting requests for exhaust pipes and this and that. He purchased smaller tools and, with a few employees and low overhead costs, started production," said Sándor Szebenyi, who took over the company eight years ago due to his father's illness and has since expanded the range of parts on offer.

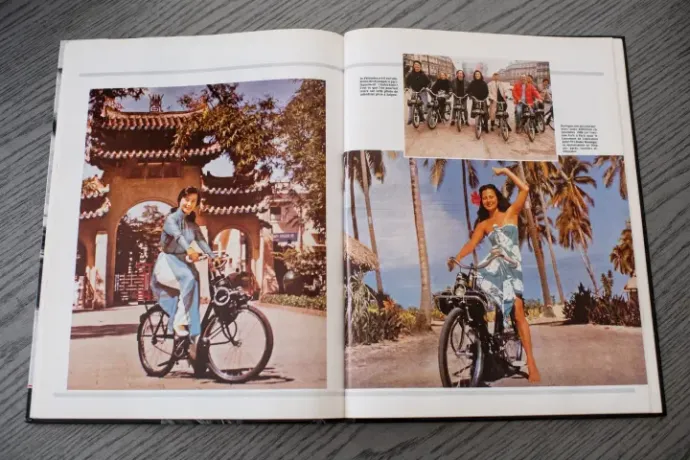

The enthusiasm for the VeloSolex has not subsided over the past 25 years.There's a high degree of nostalgia surrounding it; it's become a sort of old-timer. People have turned it into rickshaws and tandems, and some still consider it a very practical means of transportation.

Celebrities have only added to its popularity. Szebenyi explained that for a long time, two-wheeled vehicles were not allowed on the Le Mans race track, but the American actor Steve McQueen was given permission to ride his Solex between filming locations. The small motorbike also appeared in Louis de Funès films, and Robert De Niro has ridden one too. There are quite a few people in Hungary who own one of these scooters, with around 100-150 in working condition still on the roads, and in the early 1990s, Olympic champions Tamás Darnyi and Krisztina Egerszegi were also seen riding them. In a faded photograph in the workshop, we also spotted a young Tamás Deutsch (one of the founders of Fidesz, currently an MEP) in the saddle of a VeloSolex.

According to Sándor Szebenyi, of the 8.5 million VeloSolex bikes ever produced, around 1.5 million are still in use. These are highly cherished and their owners aim to keep them in working order, which is why their company is still needed.

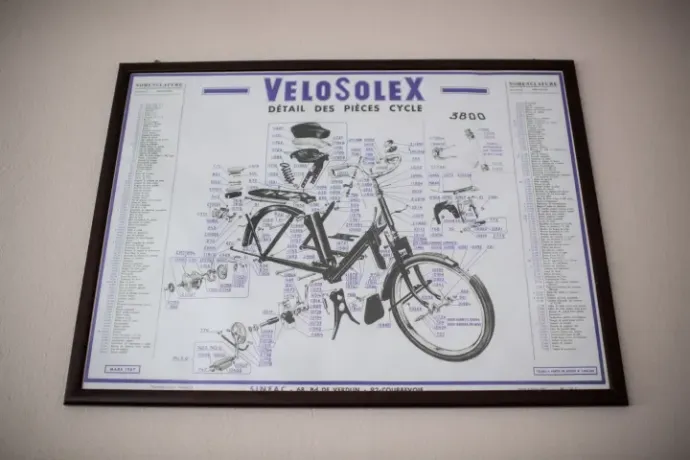

At the seemingly battered factory, they can now manufacture about 100-110 different types of parts, some of which are very complex, with a brake consisting of 60 different components and a clutch consisting of 50-52. They do the cutting, fashioning, chrome-plating, and painting on all the sheets that arrive at the factory themselves.

At the moment, there are five people working here.

"We are the biggest in the world; no one else manufactures this many different parts. There are others who try, but we are working with the original tools, based on the original documentation, following the quality standards laid down in it. In this respect, our products are not reproduced," said the company manager.

The Szebenyis also purchased the license from the original owner, which further strengthens their position, as does their decades-long experience as suppliers. They have connections with large wholesalers across Western Europe, in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and France, and they receive orders from them on a regular basis. The owner said that if they wanted to, they could assemble a complete bike in collaboration with a French partner – they have the tools for it – but the manufacturing costs are so high that it would not be worth it. In his opinion, buyers would not pay more than 600-700 thousand forints for a new Solex, and it costs more than that to build one. Depending on their condition and age, the original mopeds are now offered for sale by advertisers at prices ranging from a few hundred thousand to several million forints.

"We are proud to be keeping something that is almost 80 years old alive. If we stopped, its fate would be sealed, and the curtain would probably come down on it everywhere," Sándor Szebenyi said.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!